“The IMF’s maximum credit to Argentina… is projected to reach 1,352% of the country’s quota in 2026. This would be the Fund’s largest exposure in absolute terms in its history.”

Before we get to the meat of this story, let’s begin with a wee refresher. On April 11, as readers may recall, Argentina’s faux libertarian President Javier Milei gave a televised address to the nation. Flanked by his senior cabinet members, Milei told the Argentine people that his government had finally lifted the currency controls that had plagued the economy since 2011 so that people can once again buy dollars unhindered.

Economic stability, he said, had finally returned to the country — all thanks to another, ahem, IMF bailout, Argentina’s 23rd since becoming a member of the fund in 1956.

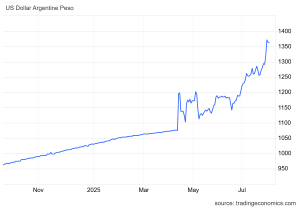

The latest $42 billion injection — $20 billion from the IMF, $12 billion from the World Bank and $10 billion from the Interamerican Development Bank — was intended to artificially prop up the peso in the months leading up to mid-term elections in October. But the peso is already in freefall, and the elections are just two months away.

As I noted at the time, this was the first time, to my knowledge that an Argentine government, or indeed any national government, had responded to a bailout from the IMF — an institution that Milei had described as “perverse” before his election as president — with jubilant celebration:

Normally, an IMF bailout is the last resort for a government that has run out of options as well as a source of great shame, not the beginning of a new golden age or the source of great pride, as the Milei government is trying to present it.

The fact that the Milei government is filled with pseudo-libertarians to whom the IMF should be anathema makes it all the more surreal. Argentina’s Finance Minister Luis Caputo, a serial debtor and former JP Morgan Chase banker who already burdened Argentina with a $57 billion IMF loan in 2018, even thanked his wife and children for their support during the negotiations, as if he were winning a lifetime award.

At the same time, some senior IMF staffers were so opposed to the deal that they were willing to walk away from their jobs.

Milei’s faster-than-expected lifting of currency controls was initially celebrated on Wall Street. Milei “is moving full speed ahead toward cleaning up Argentina’s decades-old macroeconomic mess,” investment bank UBS wrote. “The elimination of capital controls, and the strengthening of the fiscal anchor, have all surpassed even the rosiest analyst expectations.”

Time to “Take a Breather”: JP Morgan Chase

Despite all the talk of removing currency controls, there are clear exchange rate bounds for the dollar (between $1,000 and $1,450). Initially, the peso performed reasonably well, given that citizens and businesses were finally able to buy unlimited sums of dollars — albeit only digitally (the controls on cash are, if anything, tighter than before) — and send them overseas.

Pressures, however, have gradually risen, as the peso has moved closer and closer to the $1,450 upper bound. Meanwhile, increasing doubts have set in among international investors, reports Buenos Aires Herald:

´[A] JP Morgan report, titled “Argentina: Taking a breather,” suggested taking profits in long [Argentine bonds, or] LECAPs. Although the financial institution remained “constructive on Argentina’s medium-term prospects given disinflation and fiscal progress,” it warned about potential issues — namely, the fact that “peak agricultural inflows” have past, likely continued tourism outflows, potential election noise, and the Argentine peso’s underperformance, which prompted the Central Bank to intervene in the foreign exchange market via derivatives.

“With positive seasonality close to an end and elections looming, we prefer to take a step back and wait for better entry levels to re-engage in bullish local markets trades,” the report said.

In April, the firm had recommended that investors participate in short-term carry trades in Argentina after the administration lifted several capital restrictions for individuals and companies. However, in last week’s report, they said that “recent developments warrant a more cautious approach in the near term.”

The lifting of the currency controls at the behest of the IMF has enabled investors to get the money out of the country, just as happened in the 2018 bailout. In April and May, the first two months following this year’s bailout, USD 5.247 billion left the country, reports Perfil. That is equivalent to 44% of the first instalment of $12 billion issued by the IMF. This is a feature, not a bug, of IMF bailouts.

“The level of outflows in May exceeded the monthly averages of all the years of the exchange balance series prepared by the Central Bank of the Republic of Argentina — that is, from 2003 to date,” warns the Center for Research and Training of the Argentine Republic in a recent study. “It is even higher than the monthly average of 2018 and 2019, when the valuation of financial assets collapsed during the Macri government.”

If you combine the figures from April and May with the estimates from June, around $10 billion has left the country in just three months, notes the economist and former president of Banco Nación, Carlos Melconian. To put that in perspective, Argentina’s entire annual energy trade surplus is around $12 billion.

As hot money leaves the country, the pressures are building on the Argentine peso. In June, the official dollar exchange rate rose sharply. In July, the rise went almost vertical: 14% in just one month.

Last Thursday, as Bloomberg reported, the peso dropped more than 4.4% in just one day, making it the worst performer in emerging markets and rounding off a woeful month for the Argentine currency:

It has tanked by more than 12% in July, the worst monthly decline since Milei devalued it after taking office in December 2023.

The government has been building up international reserves in July, pushing pesos into the economy, amid pressure to meet goals of its program with the International Monetary Fund. The market has also seen increased demand from the private sector as businesses seek cover in the greenback ahead of October mid-term elections.

A central bank report shows dollar purchases rising in June by more than $800 million to total around $4 billion, with the number of Argentines buying foreign currency almost doubling the amount of those selling it.

“Grab the Pesos and Buy US Dollars”

The irony is that this comes just weeks after Economy Ministry Luis Caputo disparaged analysts for daring to suggest that the government has been artificially propping up the peso in a bid to contain inflation, which is exactly what it’s been doing since December 2023. The two main drivers behind Milei’s success in bringing down inflation are: a) his government’s austerity-on-angel dust program; and b) the artificial cheapening of the dollar.

This latter approach has not only made Argentina the most expensive country in Latin America in dollar terms while destroying the competitiveness of the country’s manufacturers; it has also burnt through tens of billions of dollars of central bank reserves while generating easy profits for financial speculators. It is also wholly unsustainable, as we warned in December. As Philip Pinkerton notes, the moment the economy started to grow again import demand began surging and the peso came under renewed pressure.

Now, back to Economy Minister (and former JP Morgan Chase banker) Luis Caputo.

“To anyone who thinks [the dollar] is that cheap, grab the pesos and buy [U.S. dollars],” Caputo said sarcastically a few weeks ago. “Don’t miss out on it, champ. If you have pesos, the exchange rate is free-floating, and you know for a fact it is very cheap, go ahead and buy”.

And that is what many have done. From that moment, the exchange rate has surged by AR$135, almost 11%. As the FT reports, the sinking peso presents Milei with a thorny dilemma:

The potent peso is policy. Milei is betting it will help him achieve the goal on which he has staked his political reputation: killing inflation. Argentina holds midterm elections in October and although last month’s inflation was the lowest in five years, prices are still up 43 per cent year on year.

Faced with a dilemma between reducing inflation, boosting growth or building reserves and stabilising the exchange rate, “the government prioritised inflation, which is politically the most profitable, at the expense of the others,” said Eduardo Levy Yeyati, an economist and professor at Torcuato di Tella university in Buenos Aires. “Now the other areas are screaming for attention.”

With the peso about 40 per cent stronger against the dollar in real terms, imports have surged, small businesses are struggling and unemployment has jumped to a four-year high. Despite Milei’s oft-professed desire to transform statist Argentina into a beacon of free markets, chief executives are not opening their wallets.

As the dollar rises, the risk of a sharp resurgence in inflation rises. Prices are already surging at the checkout, reports Perfil. Milei’s response has been to double down on his chainsaw austerity…

Continue reading on Naked Capitalism