As the world is gripped by a new bout of gold fever that shows no sign of abating, the environmental risks for one of the world’s most important ecosystems are rising.

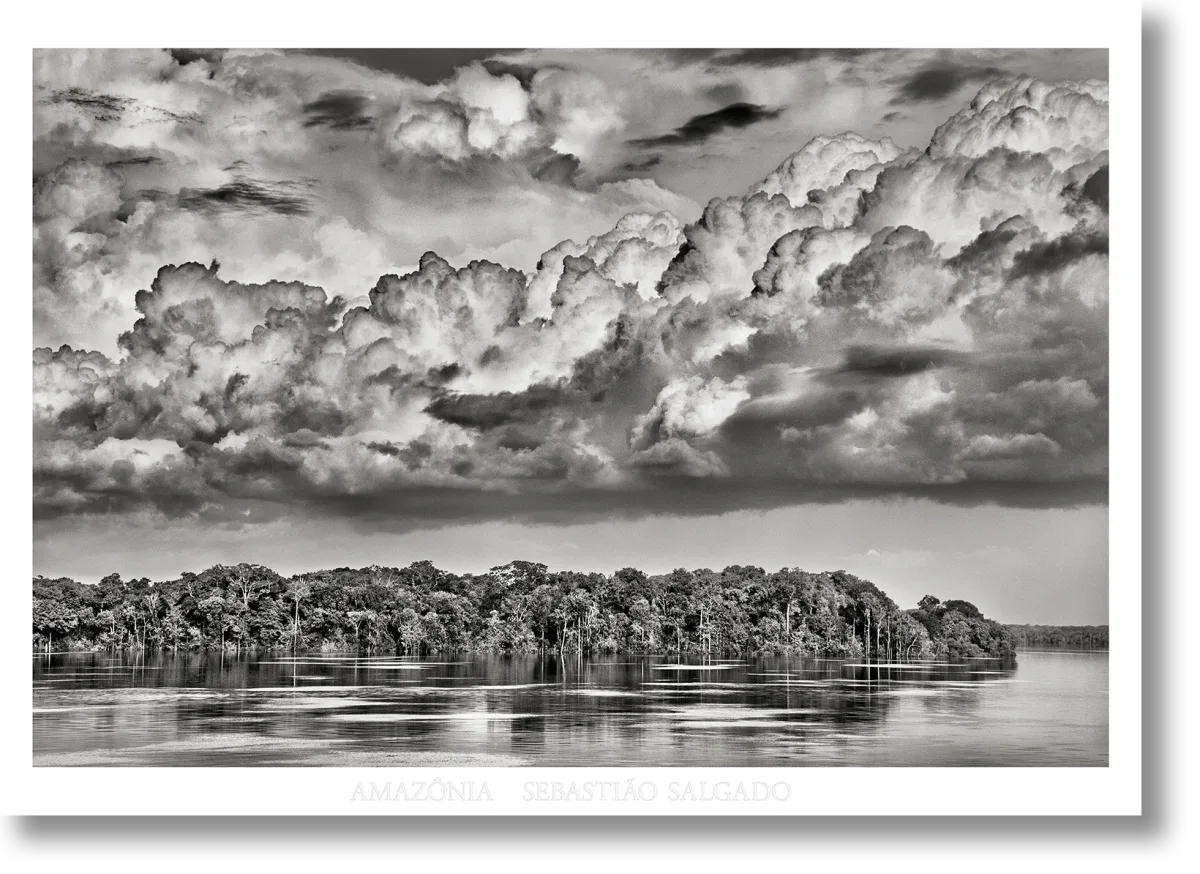

A few months ago, my wife and I had the fortune to catch the final day of Brazilian photographer Sebastião Salgado’s Amazônia at Barcelona’s Maritime Museum. It was one of the best photo exhibitions I have ever seen. The exhibition — Salgado’s last before passing away from leukaemia just a few weeks later — impressed upon me more than anything I had read or seen before just how vast, complex and fragile the Amazon ecosystem is.

Amazônia featured more than 200 photographs taken by Salgado from land, water, and air over a seven-year period, portraying the forest and its mountains, rivers, waterfalls and lakes, as well as a handful of the hundreds of tribes living in the Brazilian part of Amazonia. Featuring the sounds of the forest, the thunder of water tumbling from high, and the songs of unknown birds, insects, and other exotic creatures, it was a multisensorial experience. As my wife said, it’s worth seeing just for the cloud-studded skies, or “flying rivers” as Salgado called them.

From an economist-turned-artist whose haunting black-and-white images exhaustively documented decades of conflict in the Global South, poverty and the rapaciousness of late-stage capitalism, the Amazônia exhibition had one main overarching goal: to safeguard the world’s largest rainforest for future generations.

“We have an obligation to maintain some of these great sanctuaries, and the Amazon is one of them, to guarantee in a certain way the survival of our species,” Salgado told a press conference in Mexico City in December.

“We are losing the Amazon. Eighteen percent of the Amazon has gone. (We) have destroyed it and we may never recover it again. These photographs represent 82% of the Amazon. And one also photographs the dead Amazon, the fires in the Amazon (…) Here we present the Amazon that we need to keep together.”

The Amazon is not just a natural wonder, it is a vast socio-cultural artifact. As the exhibition points out, the Brazilian part alone is currently home to more than 300 different tribes, speaking 300 different languages. A third of those groups have had no recorded contact with the outside world. As Salgado said, “It is the prehistory of humanity that lives within this forest. But (it) is losing [its habitat].”

Global Gold Rush

Sadly, the pressures driving deforestation are, if anything, intensifying. They include a global gold rush that is turbocharging the illegal mining of the precious yellow metal under the Amazon’s rich soil.

A new paper in Communications, Earth and Environment, titled “Landscape Controls on Water Availability Limit Revegetation After Artisanal Gold Mining in the Peruvian Amazon” warns that the increasing use of suction mining for gold is not just depleting the world’s largest rainforest but is making it much harder for the ecosystem to regenerate afterwards.

Suction mining is used, often by smaller-scale operations, to blast apart soil with high-pressure water cannons. The loosened sediment is then sent through sluices that sift out gold particles, while the lighter material, including nutrient-rich topsoil, is washed away. What is left standing at the end of this process are stagnant ponds — some as big as football fields — and towering sand piles up to 30 feet (10 metres) high.

Using drones, soil sensors, and underground imaging to understand how suction mining has reshaped lands in two affected areas of Peru’s Madre de Dios region, the research team found that unlike the excavating mining used in other parts of the Amazon, suction mining leaves little behind to support new growth. From the study’s abstract:

Deforestation from artisanal, small-scale gold mining is transforming large regions of the tropics, from lush rainforest to barren collections of tailings and ponds. Natural forest regeneration is slow due to dramatic soil changes, and existing reforestation strategies are failing. Here we combine remote sensing, electrical resistivity imaging, and measurements of soil properties to characterize post-mining areas in the Madre de Dios region, Peru. We find that the post-mining landscape has dramatically changed water infiltration dynamics, driving decreases in subsurface water availability and presenting a major barrier to revegetation…. Our results suggest that access to water should be prioritized when targeting reforestation sites, potentially requiring large-scale geomorphological reconfiguration. As gold mining is expected to expand, responsible practices and remediation strategies must account for the critical yet often overlooked role of water.

According to the study, small-scale gold mining destroyed more than 95,000 hectares — an area more than seven times the size of San Francisco — of rainforest in the Madre de Dios region between 1980 and 2017. Across the Amazon, gold mining now accounts for nearly 10% of deforestation.

This is still dwarfed by the damage caused by livestock farming, which accounts for around 80% of Amazonian deforestation. However, the new paper in Communications, Earth and Environment suggests the damage caused by suction mining will be much more difficult to reverse due to the resulting loss of the most nutrient-rich layers of the soil as well as the suction mining’s intensive use of water.

Using on-site sensers, the researchers found that the sand piles function like sieves, with rainwater draining through them up to 100 times faster than in undisturbed soil. As a result, the areas dry out almost five times faster after rain, leaving little moisture available for new roots. On exposed sand piles, surface temperatures could reach as high as 145 F (60 C).

Peru is a huge player in the illegal gold business, accumulating the largest amount of gold of unknown origin exported to the world market. But Illegal mining for gold is not just a Peruvian problem.

In April, Greenpeace released a report showing that 4,219 hectares of Brazilian rainforest had been destroyed by gold miners in four Indigenous territories — Yanomami, Munduruku and Kayapó and Sararé — in just two years. While the first three territories saw a marked decline in mining activities, this was more than compensated by a 93% increase in activity in Sararé.

Below are some of the photos Salgado captured of Serra Pelada, which in the early ’80s became the world’s largest open-pit mine. At its peak, the mine drew an estimated 80,000 “garimpeiros” (independent mineral prospectors) who migrated from across Brazil to join the gold rush.

The rampant gold mining in the Amazon is also causing widespread mercury poisoning, as Amazon Frontlines reported in January 2024:

Searching for gold in the Amazon is like trying to find a needle in a haystack, blindfolded. Most of this precious metal is finely spread through sediments and soils, like tiny specks that are almost impossible to see. To solve this problem of scarcity and invisibility, miners have found a “magnet for gold” that can be chemically bonded to gold dust, creating an amalgam. This magic lodestone – mercury – is also one of the most toxic substances on Earth, which is why it is strictly controlled by the Minamata convention that was ratified by Ecuador in 2016. Despite this, it is widely used throughout the Amazon. A scientific study in the northern Ecuadorian Amazon found that 90% of artisanal or small-scale miners used mercury.

Once the mercury has been fixed to gold, it burns (as mercury has a lower melting point than gold), releasing large amounts of this toxic substance into the air. Mercury is eventually deposited throughout the jungle, adding to the unknown amounts of mercury that are dumped or dumped directly into ecosystems, making “artisanal” and small-scale mining the largest source of pollution on Earth.

However, as long as there is high demand for gold, people will find ways to get it to market, even in the smallest amounts. A database created by journalists from Peru, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Brazil, as part of the special investigation “Golden Opacity: Mechanisms Used for Old Trafficking in Latin America’’, led by Convoca.pe, suggests that at least 5,941 tons of gold were exported from those countries between 2013 and 2023. Of this amount, the origin of over 3,000 tons is unknown. Most of it was apparently laundered through Peru.

The recent surge in the price of gold and the promise of lucrative returns has also drawn new entrants into the market, including drug traffickers, according to a Bloomberg report in January:

[In Brazil, w]ildcat miners, known as the garimpeiros, have existed for the better part of a century, deforesting the land and dirtying the waters. But now, a federal crackdown on environmental crimes and a gold rally that’s sent prices to record highs has driven the industry into further darkness.

Visits by Bloomberg News to mining sites, along with dozens of interviews with miners, experts, locals and officials, unveil a world that is becoming increasingly lethal as a decades-old industry comes under the influence of drug gangs.

“The criminal organizations that have been dedicated to drug trafficking for a long time have discovered a new market,” said Andre Luiz Porreca Ferreira Cunha, a federal prosecutor assigned to illegal mining investigations across the Amazon, including the Rodrigues case. “They are creating parallel states in the middle of the Amazon. It’s terrifying.

Across the globe, if you buy gold, there’s a growing chance that you’re bankrolling bad actors.

About 20% of the world’s bullion output comes from informal, small-scale mining. The producers are sometimes called “artisanal miners,” but it’s an industry that’s typically illegal, untaxed and often in violation of environmental and other regulations. In Brazil, the miners are a major factor in the destruction of the Amazon. And globally, the sector is the planet’s single biggest source of global mercury contamination, exceeding even coal-fired power plants, according to a study from the United Nations.

Gold – often dubbed the world’s oldest currency – has for millennia attracted underworld characters. But that has been supercharged by a historic rally, which gives illegal miners greater incentive to dig it up any way they can. Spot prices jumped 27% in 2024. The metal reached an all-time high of $2,790.10 an ounce in late October and has more than doubled since the end of 2018.

A Colossal Loss of Trust

Since then, gold has continued its surge in price, reaching a fresh all-time high of $3,500.05 per ounce on April 22. The spot price is currently just over $3,300 . There are myriad reasons why the gold price has almost tripled since 2018, most of which have little to do with gold itself. Some were discussed in a 2022 article we cross-posted from The Saker.

One of the most important factors is a generalised breakdown in trust and confidence in the dollar-based financial system. In recent years, the US and the UK, the two main custodians of gold, have engaged in actions that have seriously eroded investors’ trust in their capacity as custodians, not only of gold but also of other key financial assets, including US treasury bills.

In 2019, the British government recognised Juan Guaidó as Venezuelan president, and supported his legal battle to seize roughly $2 billion of Venezuelan gold held in the Bank of England. From that point on, the gold Venezuela holds in the UK has essentially been confiscated.

Although Guaidó was ultimately unable to get his greedy little hands on the gold due to legal appeals launched by Venezuela’s real government in Caracas, the country’s gold still sits frozen in the Bank of England’s vaults — more than a year after Venezuela’s leading opposition parties voted to oust Guaidó as “interim president.” The damage this has done to the City of London’s standing as a global financial centre is no doubt considerable, noted UK Declassified in 2023:

“[W]hatever happens next, this case sets a precedent which could have far-reaching consequences: the UK’s coup weapons now include asset stripping a foreign state, and transferring those assets to political actors engaged in regime change. This will surely serve as a warning to any state which plans to store its gold in the Bank of England.”

Even before the UK decided to confiscate Venezuela’s gold, governments around the world, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe were already getting antsy about entrusting their gold deposits to the Bank of England or US Federal Reserve…

Continue reading on Naked Capitalism