This time, it’s not just Wall Street banks that should be worried about the contagion risks from a full-blown banking crisis in Mexico. So, too, should their European counterparts.

Moody’s has changed the outlook of the Mexican banking system from positive to negative due to the ongoing tariff tensions with the United States and the country’s economic slowdown. The US ratings agency cited a number of reasons for the change in outlook, including Mexico’s slowing economic growth, driven apparently by reduced public spending and market-unfriendly institutional changes. Trump-induced uncertainties surrounding trade relations with the United States are also contributing to macroeconomic pressures and lower business volumes.

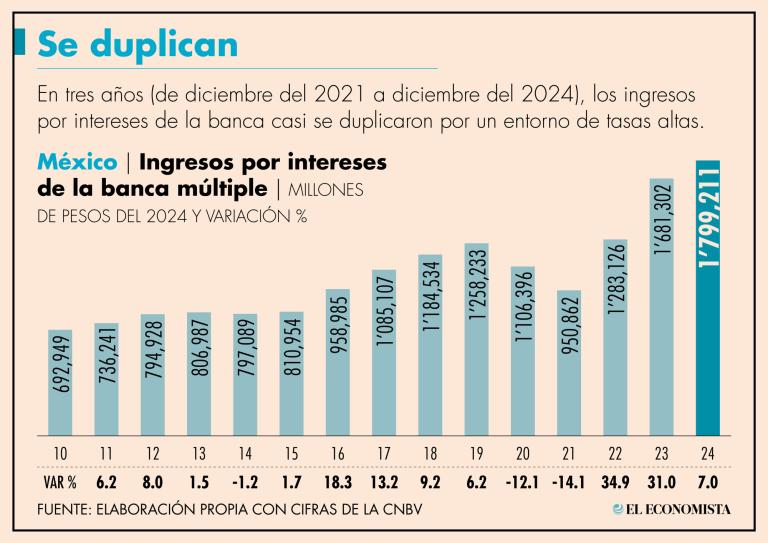

These trends are all likely to heap further pressure on an already slowing banking sector. A three-year surge in banking sector revenues, driven largely by higher benchmark interest rates, already began slowing last year, as the graph below, courtesy of El Economista, shows. Not coincidentally, in March last year the Bank of Mexico began the process of reversing rate rises. A year on, rates are now at 9.5%, 200 basis points below their former 11.5% peak.

[Translation of accompanying text: in three years (from December 2021 to December 2024), the banks’ net interest income almost doubled due to the higher-rate environment].

The Moody’s report also underscores the Mexican government’s waning capacity to provide economic support due to its weaker fiscal position as well as the potential economic impact of recent reforms to the country’s institutional framework. They include the judicial reforms that passed by a whisker last Autumn, almost sparking a constitutional crisis in the process — a topic we covered in some detail here, here and here.

The judicial reform was the foundation stone of former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s reform agenda. It was also a stepping stone, allowing for the reversal of the corporate capture and control of the country’s judiciary. Now, the Sheinbaum government can begin focusing on passing its other proposed reforms in areas such as energy, mining, fracking, GM crops, labour laws, housing, indigenous rights, women’s rights, universal health care and water management.

Suffice to say, many of these reforms are bitterly opposed by the business elite, both foreign and domestic. If fully implemented, they will limit the ability of corporations, particularly in the mining sector, to extract wealth at exorbitant social and environmental cost. For decades corporations have been able to count on the support of a pliant judiciary that has faithfully served and protected the interests of the rich and powerful. That now appears to have changed, but it is already having an impact on how foreign investors and ratings agencies view Mexico.

The Biggest Threat

Moody’s also flagged the rising risk of state oil company Pemex’s contingent liabilities materializing on the government’s balance sheet. Mexico is currently two notches off losing its investment grade rating with Moody’s and S&P and just one away from losing it with Fitch Ratings.

Granted, when it comes to the pronunciations of US credit ratings agencies, a disclaimer is needed. As was shown in the subprime crisis, when rating agencies like Moody’s were giving triple-A ratings to mortgage backed securities that were found later to be nothing but dog **** (to quote from our resident Rev Kev), the sector is riddled with conflicts of interest. It is also hard to shake the feeling that this sort of report is aimed more at putting pressure on Mexico to adopt Wall Street friendly policies than providing a true reflection of Mexico’s economic health.

The irony is that the biggest risk to Mexico’s economic health comes from the Trump Administration’s constant threats of tariffs, mass deportations and military intervention. As Moody’s warns, US tariffs could harm Mexico’s manufacturing, automotive, and technology industries. These disruptions may lead to currency depreciation, increased inflation, and constraints on interest rate cuts, which would in turn dampen loan demand. The resulting volatility in exports, exchange rates, and inflation could also reduce banks’ risk appetite.

Even though most of the tariffs have yet to be implemented for any meaningful length of time, they are already causing acute economic uncertainty between the US and its largest trade partner, Mexico. Last week, Roberto Lyle Fritch, the president of the Business Coordinating Council (CCE), one of Mexico’s largest business lobbies, warned that the persistent threat of tariffs puts manufacturing production in Mexico at risk, potentially leading to massive layoffs, a fall in foreign direct investment (FDI), and stagnating economic growth.

FDI may already be taking a hit. Blue chip Japanese companies have warned more than once that the on-off threats of tariffs is making them think twice about investing any more in Mexico.

The Japan External Trade Organization, or Jetro, a government-related organization that works to promote mutual trade and investment between Japan and the rest of the world, said that four major Japanese investments in Mexico have already been halted due to the reigning uncertainty. Three major Japanese car manufacturers, Nissan, Mazda and Honda, have even threatened to pull out of Mexico altogether.

The Waxing and Waning Whims of Donald J Trump

These cases underscore one of the biggest problems with Trump’s constant use of the threat of tariffs to get what he wants: the prolonged uncertainty it creates. Even if he keeps walking back those threats, Trump is still doing immense, if not fatal, damage to the USMCA trade deal by raising economic uncertainty to levels that many companies simply are not willing to bear. As the WSJ recently noted, Trump’s arbitrary and personalized policymaking is at odds with the predictability that businesses crave.

Trump could tamp down the anxiety by laying out a coherent agenda (as some advisers have attempted) and a process for implementing it, such as asking Congress to write new tariffs into law, as the Constitution stipulates.

But that isn’t his nature. He revels in the power to impose and remove tariffs and other measures without warning, process, checks or balances.

The result has been economic-policy uncertainty at levels seen in past shocks such as the 2001 terrorist attacks, the 2008-09 financial crisis and the onset of the Covid pandemic in 2020. Those were all driven by events beyond U.S. control. This one is man-made, and will wax and wane with that man’s word and actions.

The financial toll from Trump 2.0’s tariffs is already magnitudes higher than the impact from all the tariffs imposed by Trump’s first administration. According to the FT, the first Trump administration imposed levies on imports valued at around $380 billion in 2018 and 2019. The new tariffs already affect $1 trillion worth of imports, estimates the Tax Foundation think-tank, rising to $1.4 trillion assuming exemptions covering some goods from Canada and Mexico expire on April 2, as was initially indicated.

When the reciprocal tariffs kick in on April 2, assuming they actually do, Mexico should, in principle, be less affected than other countries since: a) it has a trade agreement with the US; and b) unlike Canada and the EU, Mexico has opted not to impose retaliatory tariffs on US goods. But Trump’s tariffs are driven not just by economic considerations but also other issues such as the amount of progress Mexico is deemed to be making on containing immigration and executing the US’ whimsical demands vís-a-vís the drug cartels.

Deportation and Remittances

Mexico also faces other risks, including the prospect of the US dumping millions of deported LatAm immigrants at its southern border. If Trump carries through on this threat, it will impose a massive social-welfare overhead on Mexico’s economy. The mass deportation of Mexican immigrants will also deprive Mexican families, and the broader economy, of some of the much-needed money remitted by workers who send what they can afford back to their families. In 2024 alone, Mexico received $64.7 billion in remittances — equivalent to 3.4% of GDP.

In some Latin American and Caribbean countries, remittances represent an even larger lifeline for the economy. They include Nicaragua, where they represent 27.2% of GDP, Honduras (25.2%), El Salvador (23.5%), Guatemala (19.6%), Haiti (18.7%) and Jamaica (17.9%). Deporting immigrants en masse will remove a substantial source of revenue that has been supporting the exchange rates of these countries’ currencies vis-à-vis the dollar.

This, together constant threat of US tariffs is not just causing (potentially irreparable) harm to the USMCA trade deal; it is also, as Michael Hudson warned a few weeks ago, threatening to “radically unbalance the balance of payments and exchange rates throughout the world, making a financial rupture inevitable.”

So far, the Mexican peso has withstood the vagaries of Trump 2.0’s economic policy surprising well, and is actually slightly stronger than it was when Trump returned to the White House on Jan 20. The currency is up 2.4% against the dollar so far this month and 3.4% over the past three months. Analysts at Barclays attribute this, in part, to the cautious, largely non-confrontational approach that Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum has taken to handling the tariff issue.

There are also other factors that should work in Mexico’s favour. For example, as the Moody’s analysts note, the banking sector retains strong capital reserves and credit loss provisions, which should support its ability to absorb potential losses. That said, bank sector profitability is likely to decline due to rising provisioning needs.

Another potential fillip is the fact that the Bank of Mexico currently holds the highest level of foreign currency reserves on record ($235 billion). This is roughly three times higher than the reserves on hand during the 2008 Global Financial Crisis.

To put that in perspective, Canada, an economy roughly 10-15% larger than Mexico’s, has total reserves of just $121 billion. The UK’s $3.31 trillion economy is backed by even less (just $94 billion of reserves). However, stacked up against similarly sized emerging economies that have also suffered debt crises in recent decades, Mexico’s reserves look somewhat less impressive. Russia, for example, boasts foreign currency reserves of almost $700 billion while South Korea’s central bank has just over $400 billion at its disposal.

Whether Mexico’s reserves are enough to avert a full-fledged debt or banking crisis, we will hopefully never have to find out…

Continue reading the article on Naked Capitalism