If one of the presumed goals of president elect Donald Trump’s first round of tariff threats was to sow discord and division among Washington’s USMCA partners, it’s working like a dream.

For the best part of the past two weeks, Canada’s political leadership has been openly discussing the possibility of throwing Mexico under the bus in a (probably vain) attempt to appease Donald Trump. Since two of Canada’s provincial premiers, Doug Ford of Ontario and Danielle Smith of Alberta, got the ball rolling two weeks ago by proposing to replace the USMCA trade deal with a bilateral agreement with the US, it’s been a massive pile-on.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said that if Mexico did not tighten its policy against China, other alternatives would have to be sought. On the same day, the leader of Canada’s main opposition party, Pierre Poilievre, said he is willing to negotiate a trade agreement with the US that excludes Mexico.

Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s economy minister, deputy prime minister, WEF trustee, project Ukraine enthusiast, with Nazi skeletons in her closet, hinted in a televised interview that the US and Canada are more naturally suited trade partners due to their “comparable economic standards”:

“The second really important guarantee of that relationship [between Canada and the US] is the economic fundamentals. The reason we got to a good place with the new NAFTA is because our economic relationship, Canada’s economic relationship with the United States is a win-win economic relationship. It is balanced, it is mutually beneficial, it is based on two countries that have comparable economic standards trading together. And since we concluded that deal, the economic relationship with the United States has become stronger.”

Freeland also said that Canada is more aligned with the US than ever before on China (and, of course, most other things), as if this were a source of pride. The Trudeau government has already pledged to impose the same 100% tariffs on Chinese-made vehicles as the US as well as 25% tariffs on Chinese steel. By toeing Washington’s line, Freeland says, Canada cannot possibly be seen as China’s backdoor into the US, adding that the same cannot be said of Mexico:

“I have heard personally from members of the Biden administration, members that have been strong supporters of Trump and his advisors, very grave concerns about Mexico serving as a backdoor for China into the North American trading space. I believe those concerns are legitimate and Canada, as a partner in the NAFTA trading area shares those concerns.”

Freeland provides no evidence to back up this claim; she just cites unnamed sources in Washington — perhaps as a throwback to her days as a journalist. She then went on to say that when it comes to the new NAFTA, the main priority for Canada is the strength of its relationship to the United States:

“It’s also really important for the United States. Canada is the largest market for the US in the world. Canada for US exports is more significant than China, Japan, the UK and France combined.”

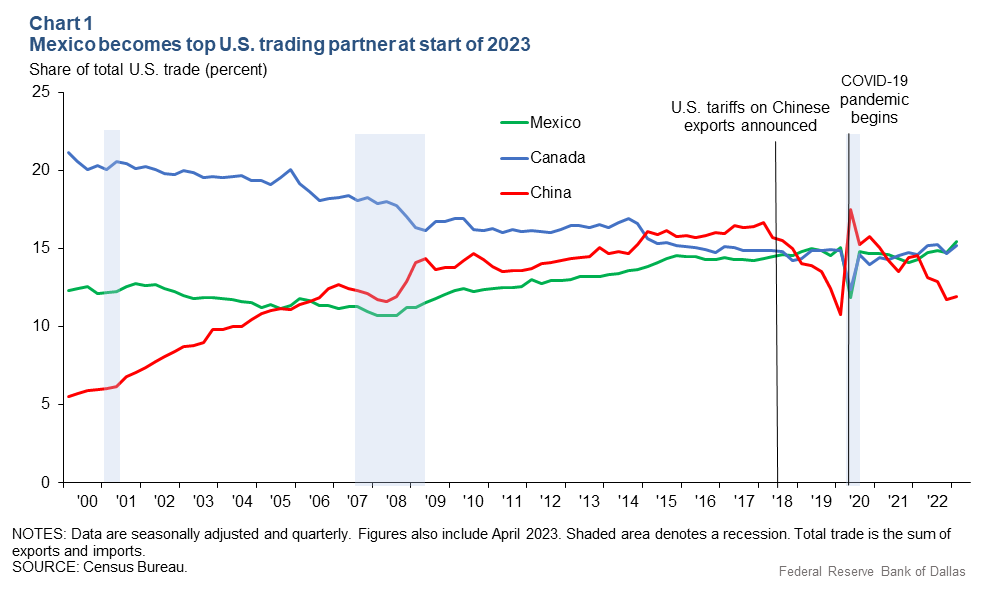

Strictly speaking, this may be true, but it is also misleading since it leaves Mexico completely out of the equation. As we reported last week, since the signing of the USMCA, Canada’s overall trade with the US has more or less stagnated, according to data from the US Census Bureau indicate. Meanwhile, Mexico has overtaken both China and Canada to become the US’ main trade partner, primarily as a result of the nearshoring trend sparked by the US’ trade war with China during the first Trump administration.

The insults have kept flowing Mexico’s way, and have even prompted a rare reprisal from Mexico’s usually calm and collected president. Yesterday, Sheinbaum said Canadians “could only wish they had the cultural riches” of her country. Probably the worst remark so far came from the lips of Ontario Premier Doug Ford:

“To compare us to Mexico is the most insulting thing I’ve ever heard from our friends and closest allies, the United States of America. I found Trump’s comments unfair. I found them insulting. It’s like a family member stabbing you right in the heart.”

These sorts of comments have been seen as a betrayal in Mexico, particularly given the lengths to which Mexico’s former President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (aka AMLO) reportedly went to secure Canada’s inclusion in the USMCA deal in the face of stiff opposition from Trump. If it hadn’t been for AMLO’s intervention, Canada may never have been invited to join USMCA. Mexico’s lead trade negotiator, Gutierrez Romano, told Canadian newspaper the Globe and Mail last week that “it is not rational to be divided against the United States”. He has a point.

But what if Canada were to carry through on its threats to kick Mexico to the curb? Would that really be such a bad thing for Mexico?

The answer is: probably not, as long as Mexico’s trade with the US remained more or less constant (big “IF”, but for the purpose of this post let’s just focus on Canada and Mexico). As we noted last week, Mexico and Canada may be partners in the same trilateral trade agreement but they are ultimately vying for the same prize — US market share — and they are both competing in the same areas (manufacturing, particularly automotive), and as Canadian Pearl Rangefinder points out in the comments below, Mexico is winning the race handily:

Mexico has eaten our lunch because it’s simply a better place to make cars in N. America – cheaper, same trade access to the American market plus better trade deals with tons of other countries around the world compared to Canada, closer to the new heart of American auto manufacturing (which is the South – not Detroit). Sombreros instead of toques. etc

In the past ten years Canadian exports of vehicles to the US have almost halved, from 2.382 million units in 2014 to 1.3 million today. During that same period, Mexico’s automotive exports to the US have surged from 1.87 million to 2.55 million. But that’s not all: Mexico exported a total of 3.3 million units last year, just over 10% of which went outside the North American market, to places like Germany, China and Brazil.

As Pearl notes, “whatever Canada can produce for export to the US, Mexico can do cheaper, starkly illustrated above with auto production. Plus Mexico hasn’t spent the past ten years pissing off the worlds largest manufacturing nation (China) while Canada has (and realistically, Canada’s best alternative to the US as a resource exporter was selling to China – completely botched because of the Meng Wanzhou/Huawei kidnapping we did at the behest of the US).”

Meanwhile, trade between Canada and Mexico is relatively modest, representing less than 5% of their respective trade volumes with the US. Data from the Bank of Mexico indicate that of the total value of Mexico’s exports, just 3% correspond to Canada, compared to 83% for the US. In fact, on balance a life without Canada would probably be broadly positive for Mexico’s economy, its workers, indigenous communities and, most importantly, its environment, given the predominant nature of Mexico’s bilateral trade with Canada: mineral extraction.

“Bad Neighbour, Worse Trade Partner”

A new in-depth investigation by the Mexican online news website Sin Embargo — titled “Bad Neighbour, Worse Trade Partner: Canadians Siphon wealth from Mexico for Next to Nothing. And They Still Wrangle on Taxes” — highlights a glaring paradox behind Ottawa’s threats to throw Mexico under the bus: doing so would jeopardise a trade relationship that disproportionately favours Canada’s mining companies, for whom Mexico has been a veritable paradise of mineral abundance and lax regulations for the past 32 years:

In recent days, a group of Canadian politicians suggested to the President-elect of the United States, Donald Trump the idea of expelling Mexico from USMCA… and forging a bilateral agreement between Canada and the US. However, the [first NAFTA agreement] together with the Mining Law (1992) passed by then-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari provided the legal scaffolding for huge profits and privileges to transnational mining companies, mainly Canadian and American.

“The USMCA has always favoured Canadian companies since 1992 because the entire regulatory framework in Mexico was modified in line with NAFTA (now USMCA),” said Beatriz Olivera, director of Energy, Gender and Environment (Engenera). “There, conditions were established allowing them to access water, territory, cut red tape, so that they did not have to carry out environmental processes and consultation of indigenous communities. The entire Mining Law of 1992 was adapted according to the standards of the USMCA just to facilitate and favour foreign investment, in this case, Canadian and U.S. investment. If we look at the mining period before the USMCA there was not all this social conflict, murders of defenders, complaints about land use and water”.

Mexico is the world’s largest silver producer, accounting for roughly one out of every five metric tons of the precious metal mined in 2021. Mexico is also among the top ten global producers of 15 other metals and minerals (bismuth, fluorite, celestite, wollastonite, cadmium, molybdenum, lead, zinc, diatomite, salt, barite, graphite, gypsum, gold, and copper). And in 1992, Carlos Salinas y Gotari’s Mining Law decreed that mining activity took precedence over all other industries and activities. Article 6 of the law reads:

The exploration, exploitation and beneficiation of the minerals or substances referred to in this Law are public utilities and will have preference over any other use or utilization of the land, subject to the conditions established herein, and only by a Federal Law may taxes be assessed on these activities.

Thanks largely to this three-line paragraph, the claims of the mining industry on Mexican land have had greater import than not just all other industries but all other human activity. During the three decades that have followed, Mexico’s federal government has been bound by law to act against the interests and rights of both private landlords and local communities in order to guarantee mining companies access to the lands upon which a concession is granted.

“No other mining law on the continent grants preferential access over any type of land use,” Jorge Peláez Padilla, a professor of law at the Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), told the investigative journalist website Contralinea in 2013. The result has been rampant expropriations of private — and in some cases communal or even protected park — land, for the sake of private mining operations.

Canadian-based firms have been the biggest beneficiaries, scooping up roughly seven out of ten licenses granted to foreign mining companies. In 2021, La Jornada reported that around 75% of the mining concessions that were granted in the pre-MORENA administrations (none have been granted since AMLO took office in 2018) were to foreign mining companies, most of them Canadian, according to data from the Ministry of Economy. As the Canadian independent journalist Yves Engler documents, all of this was facilitated by NAFTA:

There were no Canadian mines operating in Mexico in 1994. By 2010 there were about 375 Canadian-run projects. Before the reforms that came with the North American Free Trade Agreement, Mexico’s constitution dictated that land, subsoil and its riches were the property of the state and recognized the collective right of communities to land through the ejido system. Constitutional changes in 1992 allowed for sale of lands to third parties, including multinational corporations. Combined with a new Law on Foreign Investment, the Mining Law of 1992 allowed for 100 percent foreign control in the exploration and production of mines.

Today, Canadian companies dominate Mexico’s gold and silver mining sectors, extracting around 35,000 kilos of the yellow metal annually — the equivalent of 60% of all the gold mined each year. By contrast, Mexican companies extract 17,300 kilos, roughly 30% of the total. The remaining 10% is mined by US companies. For Mexico’s finances and communities, the deal has been rotten from the get-go, explains Sin Embargo.

The extraction of gold and silver from Canada’s more than 300 mining projects spread throughout Mexico has caused environmental and social devastation in communities. Despite the profits for Canadian mining companies and the damages for Mexico, protected by the USMCA, the projects contribute less than 1% of total tax revenues and 0.62 percent of secured employment per year, according to official figures analysed by the organization Engenera. Even First Majestic Silver initiated arbitration three years ago against its debt of 180 million dollars to the SAT.

That’s right: one of Canada’s mining companies is not only refusing to pay back taxes but has actually sued the Mexican State for trying to claw them back. This is all par for the course for Canadian mining companies, particularly in Latin America and Africa…

Read the full article on Naked Capitalism